Hello to my readers!

It has been a very long time since I have posted in Fashion|Academic. Indeed, my readers deserve much better! Yet there is a reason for the sparseness of my posts. First, after teaching fashion for two and a half years as an adjunct at the Escuela de Artes Plásticas of Puerto Rico, I have applied for, and been accepted to, a PhD in History at the University of Guelph in Canada. It was my utmost desire to return to school and complete my graduate education. Most importantly, the lack of scholarship about King Malcolm III, otherwise known as Malcolm Canmore,[1] propelled me to do a thesis about him. Thus, I have left behind my days in fashion to embrace life as an academic and as a Scottish medievalist.

Or have I?

While completing the major and minor seminars for my first year of PhD, I began wondering about the efficiency of my undergraduate teaching. Had I made a difference to my students when they took my fashion illustration courses? Would I made a difference to undergraduate history students when I teach the subject? How can professors, and educators in general, make a difference? After the death of Professor Louise Wilson, I realized the impact her educational (and rather legendary!) techniques had not just on her students, but on British fashion in general. The outpours of grieving students and alumni who praised her no-nonsense and straightforward teaching approach signaled an effective educator keen on extracting the best from her students. When educators believe in their students, and they let their students know that they believe in them, students react positively to teaching. Yet Western education has become an ode to automated responses, memorization exercises, copy and paste assignments. We need to change our educational strategies: we need to aim to produce professionals with deep problem-solving, critical analysis, and visual and verbal communication skills. Fashion is not immune to a redevelopment of educational strategies.

So, how do we improve our teaching techniques to get the best out of our students? Engage with them. Know them. Know their strengths and weaknesses. Creating an effective relationship with each one of your students will enhance their educational experience and, in turn, the quality of their output.

Fashion, unlike other subjects, cannot be memorized and regurgitated on a multiple-choice exam. That is one of the advantages art and design disciplines have over other liberal arts: they can only be taught effectively through practical, critical-thinking and problem-solving exercises. Through the use of critical thinking exercises, fashion teachers can engage with their students in a more direct manner.

Take fashion illustration, for example. There are multiple textbooks that show how to make a nine- or ten-head figure, how to draw faces, hands, feet, accessories, clothes, different poses. In many schools, fashion illustration is taught by either copying from the textbook or by copying the instructor’s style. Neither educational tactic allows for the student to experiment on their own. It does not allow for students to develop their strengths and address their weaknesses. It does not teach them that fashion illustration is not a mere means for communicating a design— it is an art form in itself. It requires extensive research into poses, looks, materials and techniques to do a compelling visual rendition of the style, fit and attitude a certain design (and designer) wants to convey. Fashion illustration delves into anatomical knowledge, and drawing the human body without knowing how it moves in real life makes it impossible for students to understand how to draw certain poses, or how to improvise their own. In my view, drawing with a live model is paramount to teaching fashion illustration. In many cases, we have forsaken live model drawing for textbook copying, hindering the students’ ability to critically think and understand about how clothes are drawn correctly over a human body and how different mediums and techniques best serve to represent different attitudes, fabrics, and designs. By re-taking the live model approach, fashion illustration education is made more relevant to students.

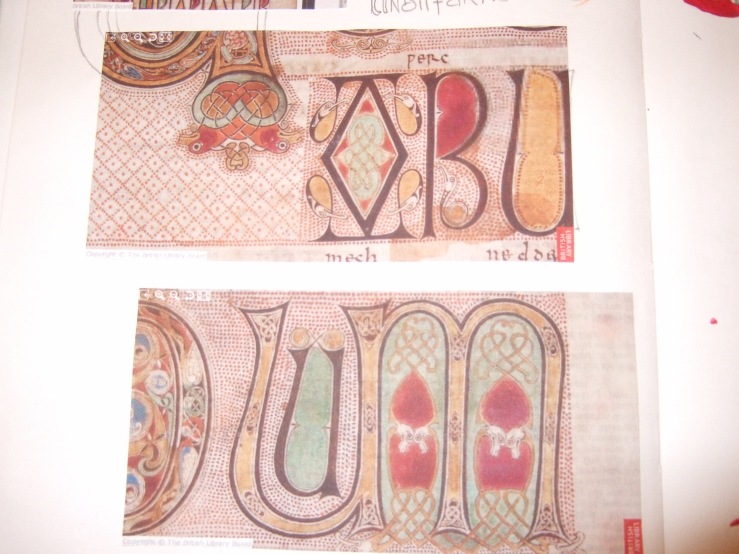

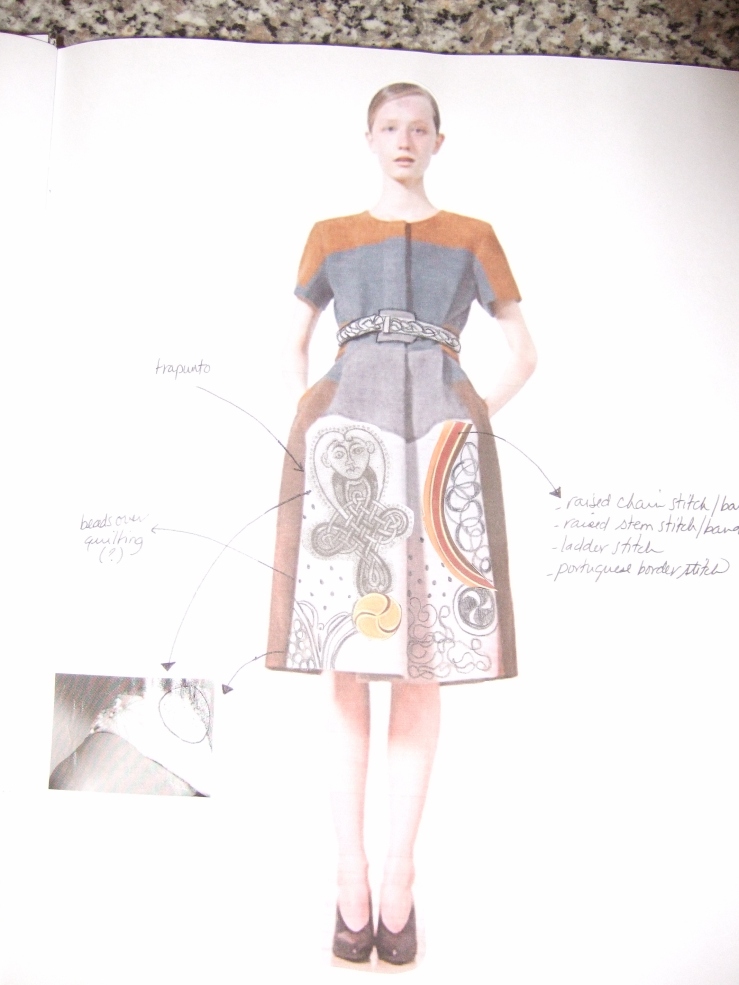

One of the biggest differences between the American and the British education style lies in the emphasis on primary research. At undergraduate level, I rarely did any primary research: students relied solely on trend forecasting publications such as Here & There and WGSN. Yet when I studied at Central Saint Martins, our course heavily relied on students doing primary research for their topics. Our sketchbooks became our best friends. Before, I only did the first designs I could think of and call it a collection. In London, I was using a full sketchbook for collection, drawing over a hundred sketches for one or two designs. The quality of my designs, and my ability to critically solve problems, improved dramatically. I used the same technique for my advanced fashion illustration classes: all students needed a sketchbook, and they would go to the library to do extensive research about how to best illustrate a given collection. They would come with piles of photocopied images from the fashion and from other art books. They would go to art stores and research which type of paper and of paints would be better for illustrating their collections. They became engaged with their illustrations; drawings were not a mere chore but an exercise on how to communicate ideas effectively through visual media.

By the end of the semester, the difference in their skills and presentations was astronomical.

I took time to see every single of my students’ ideas, suggest them different materials and techniques, and understand where they were coming from. I gave ample feedback. I knew that feedback was key to their success. But the process was not one-sided: students also learned about how I operated and what I wanted from them. They knew my standards were incredibly high: I believed in them. In the process, they learned that they could become fashion designers, even when they attended a relatively young fashion design program in Puerto Rico, where there is no fashion industry. As a school, we could not offer the amenities that came with attending Parsons, or Central Saint Martins, or London College of Fashion. But I could offer them the chance to develop their skills and ideas in par with what they did at more recognized fashion schools. And more importantly, they had the chance to believe in their talent.

Sometimes, educators do not know if they make any difference in their students’ lives. They sometimes do not know how to make that difference. Fashion is a very technical trade and fashion education is geared towards teaching students technical skills that employers search for. But we also need to teach them how to solve problems, how to think on their own feet, and how to do enough research to allow for innovation and creativity to flourish in their work. If educators decide that the way fashion education is imparted does not fulfill the intellectual development of their students, fashion education can improve. Students can improve.

It is up to us educators to find alternative methods of teaching that will engage our students better with the industry, producing innovators, not merely employees. An education where learning problem-solving skills through direct interaction with the professor will certainly improve the quality of the students’ academic experien

[1] Malcolm III (1058-1093) was the son of Duncan I and he killed King Macbeth (yes, the one from the ‘Scottish play’) in real life. He also was married to a saint: his second wife was Saint Margaret of Scotland and her life and miracles have certainly eclipsed Malcolm.